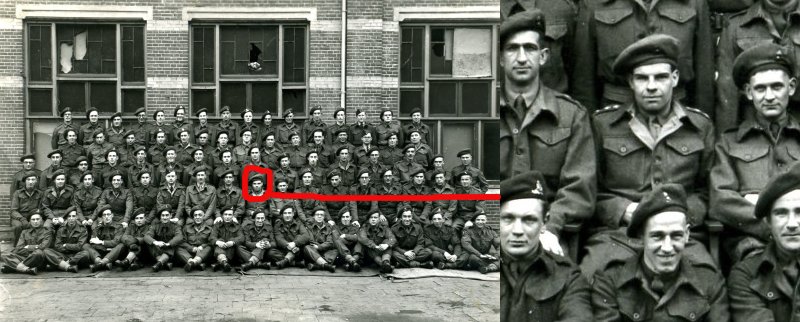

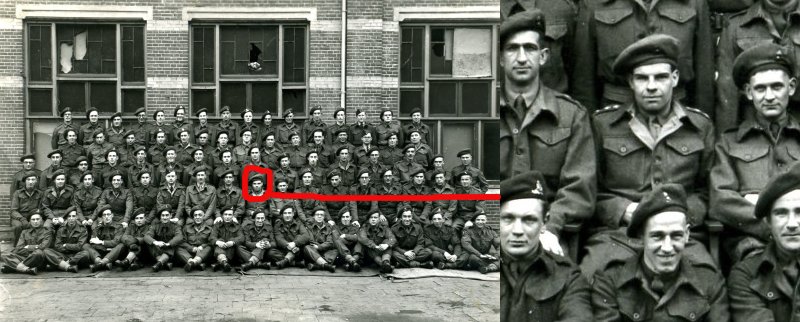

"D" Troop 9th Survey Regiment, Tilburg 1944

On May 18th [1944] the assault parties of the whole regiment loaded up our vehicles (D Troop had 6) and leaving the rest in Cobham departed with a civilian police escort into the unknown. The journey took us around London and we finished up at Purfleet in Essex. The camp was run by permanent staff and we were allotted bell tents at the bottom of an old chalk quarry. The dining tents, ablutions, NAAFI, etc were at the top which meant climbing a vast number of steps cut into the face of the chalk, a very tiring business as the weather was boiling hot. On May 26th the camp was sealed; this meant nobody was allowed in or out and all mail was stopped. This was a signal for extra activity. We were paid out in French francs, there was a new issue of battledress labelled "anti-gas", also sweet and cigarette rations, "Mae West" lifebelts, emergency iron rations and 24-hour ration packs. The anti-gas treatment to the battledress made it very smelly and very rough to the skin, I washed mine to make it more bearable. As to the 24-hour packs, they were calculated to sustain one man for 24 hours. The contents consisted of concentrated meat extract, porridge in a block which had to be grated, hard biscuits, compo tea and boiled sweets; with it went a solid fuel cooker, all packed so well that one fitted into a mess tin. In order to ensure potable water we carried tablets to purify doubtful supplies.

On 1st June we left camp and, after spending a night at another camp, on the 2nd we moved slowly to Tilbury. At this point I left my troop, a severe blow, as I was to accompany Major Humphrey as an advance party. I still feel it was just an excuse as Humph could not read a map. In fact we played no significant part.

At the docks we were told to hitch up a trailer full of ammunition and take it on board in order to tow it ashore. As we were already loaded to the gunwales I protested, but it was no good. I made a note to unhitch it as soon as we were aboard. The ship was a "landing craft tank" about the size of a pre-war cross-channel ferry boat or a bit larger.

We knew it was American as soon as we drove up the ramp as at the top we were stopped by two Yank sailors who whispered "Got any booze for sale?" All American ships are dry. Having secured the jeep on the deck I met the first mate, who introduced himself as Bill. He said a lot which I did not quite understand, and I went below where the officers had terrible quarters with anchor chains rattling all night. Next day Bill seemed upset and said why did I not come to share his cabin. I apologised and said I did not understand, neither did I know where his cabin was. He then took me to a large, well-laid out cabin near the bridge. After allocating the top bunk to me, he took me round and introduced me to all the senior crew and said I was to have the run of the ship. I forgot all about Humph down below and enjoyed walking around and spending a lot of time on the bridge.

When loading was complete we sailed down to anchor off Southend pier where we waited a few days for the rest of our particular invasion fleet to board and line up with us. I had a very relaxed time. Sometimes when Bill returned from his duties I was on the top bunk reading. He would sit at his large desk, open the right-hand cupboard which was full of American cigarettes. He would select a packet and light up. He would open the left-hand cupboard which was crammed full with chocolate. He would select a bar and throw it up to me saying "Have a candy, kid". He seemed to have no papers. On the day of the 4th June he came into the cabin armed with loads of papers and maps (sorry, charts in the navy). He then asked me where North Foreland was; I told him. South Foreland ditto, followed by the Goodwins, Dungeness, Beachy Head and the Needles. Then no more. "What's next, Bill?" "We steer at 178° (or something like that). I knew then the invasion was really on, and we were not practising any more. The reason for the charts was that the captain retired sick to his cabin and was not seen again and Bill was in charge. He was an ex-deck hand and knew nothing of navigation, hence the questions re Beachy Head, etc. I asked him how they managed to get across the Atlantic in the first place. He replied to the effect that they just followed the others. We sailed through the Straits of Dover on a gloriously sunny afternoon. On the bridge I tried to pick out the German guns that had been such a nuisance to us when at Dover. I saw nothing and not a shot was fired. On turning to the English coast, Bill said "You look a bit sad, Captain." I replied, "See that church spire? If that fell in a certain direction it would fall on my house." A bit of an exaggeration but he got the gist. "That's sad, want me to row you ashore?"

As night fell I donned my gear for landing and checked my Mae West for leaks. I had fixed this under my tunic, and had to be careful as if it was too low you became top heavy, your legs went up, and your head down, not much of a life preserver.

I then lay down and slept. The anchoring of the ships woke me and I went to the bridge. All hell was let loose, shelling, bombing, mortar fire etc; fires had started burning on land. Men were going ashore, some wading, some rowing, and some in tanks and other vehicles. We were very badly placed immediately in front of HMS Warsprite, a battleship that was firing broadsides continuously right over our heads. My hearing did not get back to normal for days in spite of earplugs. We were due to land at H+4 (four hours after the initial wave, about 0900 hours). The time went past and no signs of us landing. Bill explained that we were waiting for the "Rhinos"? to arrive. "What are they?" I asked. They were a large raft, made I think of oil drums lashed together. The plan was for us to drive down the ship's ramp onto the thing, bobbing about on the waves, and then move in to the shore and land dry. I could not believe what I was hearing. This was quite contrary to what we had planned for so long. How could such a blunder be made? I seemed also no-one had ordered any Rhinos because none arrived.

Later in the day, someone must have realised the mistake and ordered our ship to ram the shore so that we could land in the way we had trained. This threw the senior crew into confusion as not one knew what to do. Fortunately the most junior officer spoke up (he had joined the ship after completing his enlistment course, coming off Southend pier straight after being flown across from the States). Soon after, the message went out over the ship's Tannoy "Now hear this: to get these Limeys ashore we have to pump all the water out so anyone wanting to take a shower better take one now." Just imagine showering during an invasion. I was on the bridge, and the boatswain asked me "Will there be any water for the coffee?" "Yes," I replied, "I guess there will be some for the coffee." It was about this time my driver approached me. He was quite an old man, over forty, being in the last group to be called up. He explained that before the war he had no need of a car and could not drive (he was a learned scholar and composed Latin verse and wrote articles for the Spectator). I however had insisted that every man should drive, and he had enjoyed my classroom lessons. What's more, I took his passing out test myself, which gave him confidence, as did my accompanying him on his first drive through water. He would however be very pleased if I could see my way to driving the Jeep ashore. I assured him he would be OK, but before he had a chance to change his mind I agreed. My mind being focused elsewhere I forgot to cast the trailer adrift so the powers that be got their precious ammo ashore.

Ashore it was surprisingly orderly; land that had not been cleared of mines was taped off and a sign confirmed we had landed on the correct beach. Signs to the various rendezvous were all correctly aligned; they just pointed inland. I found our spot, which had me worried as it was an empty field; a second assessment and the arrival of Lieut Rodwell (a flash spotter) confirmed my judgement. There was plenty of activity going on around us with jeeps fully loaded with supplies going forward and then returning with the wounded. A rack had been fixed on each vehicle on which three stretchers could be placed. The lesser injured rode in the body of the truck. Did I spot the stretcher cases being covered with a cover displaying a Red Cross?

No further men arrived and when it was quite dark Roddie and I decided to turn in together using our single blanket (one each) to give us better cover. We chose a ditch with the jeeps visible alongside; in the hope that tanks might see them and give them a wide berth. We each had a bottle of Scotch and Roddie wanted to down his, but I told him it might be required for more important treatments later, so we each had a good draw on his and fell asleep. When we woke my troop had arrived and was busy dewaterproofing. Roddie was surprised they had not wakened me. My retort was they knew what to do and they would not be thanked for spoiling my beauty sleep.

Some time later Humph arrived following some of our vehicles. I would not care to speculate how much was by chance and how much by design that we had got separated. My troop and I had been on different ships as I was to accompany Humph as advanced party (almost certainly to read his maps for him). He immediately asked why I was not doing my reconnaissance. "What reconnaissance?" "The one for which we did a T.E.W.T. (paper exercise) on board ship." I pointed out it was quite pointless as (a) we did not know if the ground had been captured, (b) whether the Germans had any guns to fire, (c) whether we had any guns to fire back and (d) we had no orders to deploy. He made all sorts of remarks such as dereliction of duty so just to shut him up I set off on a motor cycle. There was little room on the road for jeeps etc, and only one man would be exposed. I threaded my way through the chaos and reached more peaceful areas. It was a fine early morning and the birds would have been singing in the hedgerows if the natives had not eaten them all. Then it got eerily quiet so I stopped in a village square to sum up the situation. I was immediately surrounded by gabbling schoolboys. My school French was well behind me, but a man appeared saying he was a schoolmaster and he spoke good English. I asked the inevitable question "Are there any Germans about?" He said they had all pulled out the afternoon before. Just then some more boys ran to me from the opposite corner of the square. I thought they said there were some Germans behind the wall, but the schoolmaster said that they said there was a German stronghold but no Germans. Just at that moment all hell was let loose, machine gun fire etc, and a Canadian Bren carrier burst round the corner and joined me. One of the crew was badly injured and barbed wire was wrapped round the tracks. I pulled out my revolver and was about to shoot the schoolmaster but he had disappeared into the village. I wanted to go after him but the Canadian Capt was wiser than me. He said if no German soldiers remained there would be soldier's wives (German and French) and I would not come out alive. He explained that he was a forward scout for the Canadian Div and was spying out the land in preparation for the next attack, and we were definitely in enemy territory. So the best thing for me was to come back with him and report. This I did only to be railled at by Humph with such things as "desertion", "cowardice". My move was to say "Sod you, I am off to see the Colonel." On reaching RHQ the temperature was raised still higher as Uncle, rather than being seated on the grass preparing his 24-hour emergency rations, was at a table eating a cooked meal with knife and fork (probably from the farmhouse). I told him what I thought of his battery commander, but he did not rise. Instead he pushed his moustached upper lip forward and said "I have received orders from Corps. We are to give up our role as surveyors and become infantry men. The job was to clean up all territory already captured so as to have the real infantry to prepare for a new assault." Then he said to save time he would give me my own area. What he really meant it would avoid me having to take orders from Humph. I withdrew thankful that I had not been arrested for mutiny, only to find on return to the troop that Roddie (my night companion) had had his foot blown off by an S mine (anti-personnel) and the Germans had captured him. We were told they were holed up in a cave in the side of a hill, so we brave British soldiers persuaded some French Canadians to raid the place. It was not a cave but a tunnel and the Germans ran out at the far end leaving Roddie behind. We were able to get him stretchered to a Canadian field hospital for transportation back to the UK. His treatment was delayed and I think in the end he lost the whole of his leg.

The next day we were ordered to march inland 4 miles to the village of Fontaine-Henry a hell-hole of a place, metal being fired at you from all angles from rocks, caves and wherever. We did not stop long, the French Canadian infantry decided to withdraw and we concurred, going back about 2 miles to Reviers and digging in. It was a mystery who gave the orders to advance. The Troop thought it was Humph's map reading skills and composed a song about the ill-fated venture. It was often sung at concerts, but Humph seemed to show no sign of embarrassment. All I can remember now was the last line of the chorus "On to Fontaine-Henry where no-one's been before." On June 12th [1944] (the day before my birthday) we moved forward again and prepared for a SR deployment. It was at le Fresne-Camilly and our first under battle conditions. It was not our fastest taking just over 2 hours. Most of the outstations had a very nasty time, and had to withdraw for some periods at night. Laying and maintenance of cables was most trying; there was so much traffic, especially tanks. Also troops were not familiar with our listening posts which looked like large beehives and they often got blown up by our troops. In the 30 days it was in operation we recorded 193 locations of which a good number were A or B (A was within 100 yards or better). This base also marked the first receipt of letters from home, the arrival of our 60% party, and the issue of compo food packs. These were boxes containing 14 men's rations for a day or 14 days for one man, mostly tins, a welcome change from the emergency packs. They also contained sweets and 70 cigarettes (5 a day) which was to be our ration of cigarettes right through hostilities.

There was an unfortunate incident at this base which under anyone other than Uncle (our CO) might have been curtains for me. Immediately behind us was a very important Headquarters. Division? Corps? or maybe even Montgomery's HQ. The area was constantly being hit by large artillery shells. Naturally they thought it was coming from the front and we being in front should be able to pick them up. It must be remembered this was our first working under battle conditions. All previous work was on ranges without the disturbance of mortars, machine guns, as well as other artillery. This was all recorded on our film which made picking out individual gun sounds difficult, and we were unable to find any big guns. In fact we were so sure there were none we said so. Humph came into HQ and implied we were inefficient and ought to do better. I gave him some film. I knew it was a useless exercise. We would have got more from it if we had put it in a pianola. I visited C Troop on our left who were looking at right angles to us across the Caen canal, but unfortunately they had suffered heavy shelling and sustained several deaths so I got nothing there. Likewise when I visited the Sound Rangers on our right. When he (Humph) returned the next day with similar comments, but this time saying Uncle was also unhappy and was hinting at making changes, I saw red. "Why doesn't he come himself to tell me?" I marched off to the RHQ to confront him. His HQ was in a walled garden and when one closed the door it was like passing from hell to heaven, it seemed so quiet and peaceful. I let rip at Uncle telling what I thought of his battery commander and concluded by saying that I would not be sorry to go but if he was thinking of promoting Willie or Charlie to my post forget it as they were as fed up as I was. I turned on my heels and left expecting the adjutant to be sent after me to place me under arrest. When I got to "hell" and was driving back my thoughts dwelt on the good times I'd had with Uncle, especially our time at Dover. Then a thought struck me. What if these guns really were long range; could they be the same guns as we faced at Dover? At this point things probably get into the realms of fantasy. Did it happen or did I imagine it and over the years I have come to think of it as fact? To continue: when I got back to HQ I ordered a new plotting board to be made, but facing the coast, with the Straits of Dover guns still in mind. I looked for the characteristics on our films of the cross-channel guns which I could remember as very distinctive. We managed to get a plot on the coast about 22 miles away, outside the theatre of operations, just the range of the guns at Dover. It was fortunate that Uncle had been with me at Dover as he agreed we may have found the gun (or guns) troubling the important HQ. For some years I thought the facts were as stated, but I cannot recall any action being taken, probably our situation changed and new positions taken up. There is now no-one around who can confirm or deny this story and I think I am coming round to thinking it was just me fantasising, very probable given the circumstances.

From this time onwards we seemed to be constantly in action, it got quite routine. I am not going to record every deployment in detail, it would be much too boring and probably not understood, and it is set out in much detail in Sgt Bod Watkins account "From Knook to Mehle". I will just pick out incidents which I feel may be of interest.

We were kept fully engaged being passed from one division to another, in fact we must have worked with all of the divisions in the British and Canadian armies plus one American, the 72nd Timber Wolf Division.

I think our work was appreciated and our name got around. Unfortunately it was known as Bromley's Troop. We had confirmation of this almost at the end of the campaign. We were at Tilburg. The Regt received orders for D Troop to go up to beyond Nijmegen to help a division that was having a rough time. I was in the UK on leave, so Charlie led the troop. When he went to receive orders he was told by the General (or his CR) that he had asked for Bromley's troop, not his. Charlie had to explain, and he even told us about it. It must have taken something for Charlie to tell us bearing in mind the little chip he always carried on his shoulder. We had one piece of luck which enhanced our reputation. The troop was ordered to deploy on a second base whilst we were still in operation on the current one. This was a pretty tough order and it was required to be operational immediately as the new division was getting very heavy shelling particularly at night, and there is nothing more upsetting to the average Tommy than to have his sleep interfered with. At nightfall we went into action on the new base. It was not fully complete, two of the six microphones (listening points) were only on map spots and not surveyed in, and some were on radio and not line. Believe it or not, not a round was fired that night and everyone, including the senior officers, slept well in their trenches. We had worked a miracle and we were revered by everyone. If only they had used their brains. No German guns fired so we obtained no locations and no Allied guns had replied so as to keep the German heads down. For some reason the guns had been pulled out or had remained silent. Fortunately I think it was the former as the troops did not get troubled again. My boys were too clever and enjoyed the praise too much to let on.

On July 23rd we were called upon to set up our third base (the second only lasted a few days) at Giberville, which was by no means a healthy place. Apart from shelling and mortaring, we had to contend with numerous dead and decaying animals which in turn brought swarms of flies and mosquitoes. The cattle were blown up to an enormous size, so to try to reduce the volume of digging shots were fired into the stomachs, but the smell was awful so we tried burning, but the smell was even worse. Worried about dysentery, I used to inspect the men's mess tins and eating irons before their meal. This did not go down too well with such people as the university graduates but at least it kept us pretty free of stomach ailments. How the Germans could have lived in that filth I cannot comprehend. Maybe they had too many of their dead to bury in the hard ground.

We travelled west, setting up a few bases until we arrived at Maneglise a few miles from Le Harve. This was no great distance from Fecamp the home of the Benedictine monks who produce the wonderful liqueur of that name. Although the monks wanted to do business with us they did not wish to deplete their stock too much and limited supply to "un soldat une bouteille". It was ingenious the disguises some of the troops adopted to get more than one bottle.

Le Harve held out and certain troops (D troop included) were left behind to take the surrender. We were on the east side in a perfect position overlooking the harbour and with a favourable wind, in the eight days we obtained 83 locations of which many of accuracy A or B. I think it was Willie and I who visited the town on its fall and could find only four gun positions we had not picked up, and there was no certainty that they were not put out of action before we arrived.

By Bod Watkins diary, we packed up at Le Harve on September 12th; we were well and truly behind the main battle lines and we marched straight off to Belgium. I was terribly disappointed as I had hoped to travel up to and through the channel ports in the Dover Straight so that I could have a good look at the guns that had played an important part of my life from the summer of 1940 until February 1942. If the towns of France were very dull and run-down, Brussels by contrast was like Oxford Street during the Christmas rush, bright lights and everything in the shops. Life looked very normal and I swear that the trams in one town (if not the capital) ran from our lines and on into the German territory. In fact on one occasion I went by tram to visit one of our Advanced Posts and when I alighted the tram just went on. I think the Belgians learned how to live with the Germans. I found no difficulty in buying a bottle of Chanel No 5 to send to Christine at Esher. The wrapping paper I used was recognised by Pete (Christine's mother's boyfriend, the pub landlord). His comment was that in the first world war it was brown and much coarser. It was lavatory paper, and as all paper had to have a number, it was known as "Army Form Blank". In our day it was about four inches square, white and smooth, and if you could get a Bulldog clip it made a handy message pad.

Staying back at Le Harve we rather lost the thread of things and we were not back into action for 14 days. Time to clean up and check our stores, run a few passion trucks into local towns and find time to beat our survey colleagues E Troop 5 goals to 1 at football. Bod in his history even reports we had an issue of blanco. What were our feelings on leaving Normandy? I found it very much like my native Kent, arable farming, livestock and orchards. The natives were not hostile, but not (with exceptions) exactly friendly. Some complained and said why did we invade when it was time for their harvest. Our reply was to the effect that we were not too anxious to come when the snow was on the ground. I vowed that I would never drink Calvados - that strong spirit made from apples - again. It was not due to suffering from an excess of it as you might imagine, but the result of seeing it being made. On one farm near our waggon lines, when the apples were ready, the farmer chased the chickens from the barn and swept the presses with a yard broom to clear away the hay, straw and chicken droppings. The presses were then filled with apples straight from the orchard and put to work. The first juices made a good job of cleaning out the troughs, but I was disgusted that it was not run to waste. Perhaps it was reckoned to improve the flavour. It reminded me of Church Farm when we went to use the mills and cutters with which we prepared cattle food.

From the Brussels area we pressed on towards Antwerp and the Dutch border, and beyond. Place names such as Baal, Oostmalle, Westmalle, Camphout and Vosselaer spring to mind. At these and others we established bases. While at the last in off-duty moments we could get into Antwerp which I found a much better place for the off-duty soldier than Brussels. At Baal we stayed just one night but it coincided with an annual fair. Every family had to provide a cake or something. We all joined in and it was most enjoyable. I had the privilege of taking the daughter of the cafe owner where we billeted for our stay. In Antwerp I was lucky to escape getting into trouble. Gerry (our RAF meteorological officer) and I visited a bar (the Blue Lagoon I think). It had a reputation and was out of bounds for all troops. It was this that made it attractive. Unfortunately whilst we were there it was raided by the police, Belgian civil police together with US and Canadian army police. Guards were put on all exits. At one door, Gerry and I were the only British, and it seemed we were the only ones in the place, but we could not be sure there was such a scrum. The US sergeant said we posed a problem as the British police (the red caps) had failed to turn up. After chatting for a while I suggested his problem would vanish if he would just open the door for 2 seconds. He saw reason and Gerry and I were quickly in a back street. It was full of hoses and fire engines. There had been some sort of air raid while we had been inside - a flying bomb or a rocket. In spite of its attraction, Antwerp was a dangerous place to be, and one's pleasure was often spoilt by falling masonry and shattering glass. Everyone however tried to live as normal a life as possible and I remember in one village I had the odd experience of seeing a farmer putting glass in the front of his house while shelling was blasting them out at the rear.

We tried to get into Holland towards Tilburg by attacking, with the Polish division I think, up through Turnhout. The going was very hard although we got good results at our base at Hegge. I cannot recall the exact circumstances, but the Poles either withdrew or were held up. Meanwhile we were moved westward and joined a Scottish division and got into Holland via Roosendaal. From here we turned east and reached Tilburg via Breda. We did not realise it at the time, but Tilburg was to be the last days of sound ranging for D Troop.

Reading this it seems very bland, as if nothing much was happening. In fact it was quite the reverse, in some respects the toughest in the campaign. Strange to think Antwerp was close by where we enjoyed the odd hour in the cafes and bars.

It was for my efforts in this area that I was awarded the Military Cross. They were traumatic times and I cannot remember too much about it, and am at a bit of a loss to explain things in detail. I have often been asked for details, particularly by my friends in the Rotary Club of Walton. For their enlightenment I penned an article for their magazine and it might be appropriate to insert it at this point. As I say, on some things I am vague but what is written is the truth and not my imagination.

From Villain to Hero in Four Weeks

"D" Troop 9th Survey Regiment, Tilburg 1944

We arrived at Tilburg on 12th November 1944 and did not leave until 28th May 1945. We had three bases laid out south of the river Maas, the job of the troops being to prevent the enemy from crossing the river. C Troop (our opposite number in A Battery) were stationed in Breda and between us we manned the bases as required. Working in shifts gave us a certain amount of free time and we quickly integrated with the population. For us it became somewhat similar to Middleton as many of us had our feet under a Dutch table. In fact I think we had as many weddings as we did at Middleton. Charlie wanted to organise a dance and I agreed subject to a partner being found for me. He was billeted with a family with three grown-up girls who had plenty of contacts. The one they dug up for me was plain, stodgy, well-corseted, and complete with phrase book. I am no dancer but I spent my time dancing round her. After that experience I said no more, unless someone better could be found. Charlie's partner said she had been misled by Charlie who referred to me as the old man, a common term for any immediate boss. Having met me she knew exactly the one for me. How correct she was. As soon as I rang the bell at No 100 Nieuw Boscheweg a vision in white glided out of the door and into the jeep. We got on like a house on fire, she was much like Lena who I was to be lucky to meet later on, perhaps a little more vivacious, bold, cheeky? She had a very nice family, mother, father and two younger brothers, and apart from anything else it made a nice, civilised sanctuary away from military life. It was not all sitting on the settee and talking to mother. The Canadians opened a night club and most nights when I was free found Annette and I there. There was a live band, dancing, drinking and some food; this was a useful supplement to Annette's meagre Dutch ration. Her mother once told me the meat ration was just about enough to make the gravy. Annette was an excellent dancer which was good as I was very poor. It is said poor dancers always got on well with a really good dancer as she always had her feet in the right place to avoid those of her partner. We did all the steps and some not in the book. Occasionally we even did an impromptu solo much to the amusement of the band leader.

Annette

Annette

It was quite a severe winter and when a large lake froze over and this was followed by snow, the troops packed the snow up into a large pile in the middle of the lake and Annette taught me to skate. Once she and her friend took me in hand in order to speed up my skating. We certainly speeded up and as we approached the pile of snow, one went one side and one the other, leaving me to crash into the soggy mass, much to the enjoyment of the troops.

It was at the time of the Ardennes offensive (the Battle of the Bulge) when the Germans made a desperate attempt to break through and push towards Antwerp (I think). It did not affect us except we were ordered to carry arms even when off duty, and evening activities closed down a bit. Annette and I thought we would try another club which had opened at Nijmegan. It was no better than the one in Tilburg, but a change. On the way back there was a very long column - mostly tanks - moving in the opposite direction off to repulse the enemy. The tanks had paddles sticking out from their tracks, I guessed it was to reduce their bearing pressure to assist over boggy surfaces, or maybe something to assist in snow. There were of course no lights, but somehow I suspected that a tank was coming up using our part of the road in order to overtake. I pulled to the side as far as possible alongside the ditch and amongst the trees. No sooner had I stopped than the tank rushed past, and one of its paddles caught a tow-rope which I had tied to the side of the jeep. The rope was thrown into the air and came down on the bonnet of the jeep. It was Annette's side, but you could not see daylight between the two of us as we pressed against the opposite side. We remained like that and not just for the pleasure of it. I thought afterwards what a news story that would have made, British officer and Dutch girl crushed to death under an Anson tank. We stuck to Tilburg after that.

Our relationship became quite serious, and Annette tried to work a scheme to get to England. I told her how to find Church Farm, but goodness knows what both parties would have thought when a sophisticated young lady who had never done a day's work since leaving school came up against my mother. About the time of my leaving Holland for Germany we both began to see sense. It would not have worked. I would have no means of supporting her for at least three years after demobilisation and then probably not as well as she could expect in her own country. What was more was the fact that her family were Catholic, of which there are few in Holland, but they are (or were) very devout, perhaps bigoted, and I could foresee Annette being ostracised from her family which I am sure would be difficult as the family were very close. I could not picture life in England for her alone in a foreign land. The matter was in suspense when I left, but it was cleared up on the first occasion that I returned from Germany and we agreed we would remain good friends for the rest of our lives. We still exchange news and a Christmas card each year. I am pleased to say we both made excellent marriages, and I have no regrets whatsoever. I was invited to daughter Nicole's wedding (the family now live in France), but it was on the same day as that of Frank's granddaughter Sara's first wedding.

Annette

Annette

As a keepsake for each of us I was taken to a grand photographer (a friend of the family) to have a portrait done. I was pushed around, my hair was altered, angles carefully considered, and it was the end when Annette took out her compact from her handbag and powdered my shining nose. I sent mine home for sake keeping. Mother never said much except farming news in her letters, the sting usually came in the PS. This time no mention of the photo until the PS "Thank you for the photo of the good-looking officer, but who is it?"

©2003 Ron Bromley

2003-02-13..2015-04-13f

index